Brief

Look again at Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photograph Behind the Gare Saint-Lazare in

Part Three. (If you can get to the Victoria & Albert Museum in London you can see

an original print on permanent display in the Photography Gallery.) Is there a single

element in the image that you could say is the pivotal ‘point’ to which the eye returns

again and again? What information does this ‘point’ contain?

Include a short response to Behind the Gare Saint-Lazare in your learning log. You can

be as imaginative as you like. In order to contextualise your discussion you might

want to include one or two of your own shots, and you may wish to refer to Rinko

Kawauchi’s photograph mentioned above or the Theatres series by Hiroshi Sugimoto

discussed in Part Three. Write about 150–300 words.

While going through the materials provided for this part of the course, I have recalled reading a short story “Sundog Trail” by Jack London which interestingly develops the visual incarnation of the concept of a story described by Walter Benjamin in his essay ‘The Storyteller’:

“The value of information does not survive the moment in which it was

new. It lives only at that moment; it has to surrender to it completely

and explain itself to it without losing any time. A story is different. It

does not expend itself. It preserves and concentrates its strength and

is capable of releasing it even after a long time.”

(Benjamin, [1936] 1999, pp.89–90)

The storyteller in Jack London’s short story is a painter. He is trying to explain the idea of a picture to his companion Sitka Charley, an Indian. The storyteller describes Sitka Charley in the following words: “He visualized everything. He saw life in pictures, felt life in pictures, generalized life in pictures; and yet he did not understand pictures when seen through other men’s eyes and expressed by those men with color and line upon canvas.” He further explains to Sitka Charley what are pictures: “You saw something without beginning or end. Nothing happened. Yet it was a bit of life you saw. You remember it afterward. It is like a picture in your memory.”

Sitka Charley agrees that pictures – fragments without beginning or end, but having an essential “now” are a part of life: “Yet is it a true thing. I have seen it. It is life… pictures not painted, but seen with the eyes. I have looked at them like through the window at the man writing the letter. I have seen many pieces of life, without beginning, without end, without understanding.”

Sitka Charley then tells a story that he witnessed, of a young woman and a man pursuing another man over thousand kilometers of snow-covered tundra in Alaska at great cost and hardships, ultimately overtaking and killing him. He interestingly depicts the story in “picture manner” using the present tense: “Canoe smash and stop right at Dawson. Sitka Charley has come in with two thousand letters on very last water.” “And then we come upon the man with the one eye. He is in the snow by the trail, and his leg is broken.”

The story concludes with the following dialogue:

“You have painted many pictures in the telling,” I said.

“Ay,” he nodded his head. “But they were without beginning and without end.”

“The last picture of all had an end,” I said.

“Ay,” he answered. “But what end?”

“It was a piece of life,” I said.

“Ay,” he answered. “It was a piece of life.”

And this what photography also is. Pieces of life compiling an astonishing mosaic. Each piece leads who know where. And the more experienced we become, the higher is our appreciation of this beauty.

The Henri Cartier-Bresson’s iconic photograph “Behind the Gare Saint-Lazare” is great in its capaciousness as “piece of life”. “Pivotal point to which the eye returns again and again” in my opinion is the silhouette of the leaping man, which is effectively (from compositional point of view) reflected in the water. Judging on the figure of the man we can see that he leapt from couple of meters to the left – a good leap – and is probably going to land directly to the water. As I assume, a man should be in a hurry to dare such a leap. As we now, Gare Saint-Lazare is one of the busiest railway stations in Paris. So it could be that the man was trying to catch the departing train?

Why was he in a hurry? Who knows? Maybe it was the last train on that day. Maybe he was trying to get home to his sick wife? We will probably never now, but this does not prevent us from fascinating this “piece of life”.

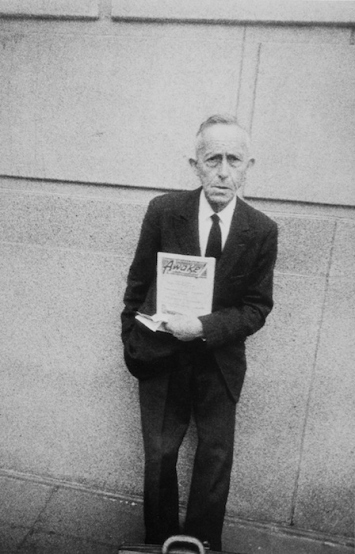

I remember taking a photograph of a simple street scene on one of the ancient squares of the city of Tashkent (Uzbekistan). The man stopped a young woman on the street and started a conversation. I do not speak Uzbek, so I had no idea what they were talking about. They could be neighbors, discussing weather. Or he could be making a compliment to the passing young and attractive woman. Countless possible scenarios, but the viewer of such photographs never knows which one is right. It is just “a piece of life”, beautiful by itself.